The Beecher-Tilton Scandal

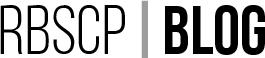

THE WORLD IS MY COUNTRY- TO DO GOOD IS MY RELIGION - Isabella Beecher Hooker

The Beecher-Tilton scandal, a shocking allegation of adultery between prominent supporters of the suffrage movement, captivated 19th century Americans for the three years between 1872 and 1875. It opened the suffrage movement to charges of free love, or sexual relations outside of marriage. The affair was exposed in 1872 by Victoria Woodhull, a prominent suffragist who was friends with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The couple at the center of the affair, Henry Ward Beecher and Elizabeth Tilton, were also deeply involved in the suffrage movement. Henry Ward Beecher was a famous preacher and the ostensible head of the American Woman Suffrage Association. His sermons attracted 19th century American luminaries such as Walt Whitman, Abraham Lincoln, and Mark Twain, earning him the label “the most famous man in America.”[1] Elizabeth Tilton was the wife of Theodore Tilton, a major supporter of the National Woman Suffrage Association.[2]

The scandal received nationwide news coverage from 1872 to 1875 detailing the affair and the various criminal, civil, and church trials of Woodhull, Tilton, and Beecher that followed. As a result of publishing an article about the affair in her newspaper, Woodhull was imprisoned for six weeks for sending “obscenities” in the mail. The widespread discussion of the affair in the newspapers led to the passage of the Comstock Law, anti-obscenity legislation with far-reaching ramifications, including making it difficult for women to write and teach about birth control well into the 20th century.[3]

The Isabella Beecher Hooker Collection, housed in the Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation at the University of Rochester, encompasses more than two hundred letters and documents of this 19th century suffragist. Among its notable contributions, it yields fresh insights into the Beecher-Tilton Scandal. Beecher Hooker was closely connected to the couple at the heart of the scandal; Henry Ward Beecher was her half-brother. She corresponded with many in the suffrage community drawn into the scandal by the press. Through her correspondence, the reader watches the scandal unfold from well before it was in the public eye. Isabella Beecher Hooker is forced to choose between remaining loyal to her brother or defending the suffrage movement against accusations of free love.

Born in 1822, Isabella Beecher Hooker helped pass a bill in Connecticut that gave married women property rights, and she was one of the founders of the National Woman Suffrage Association.[4] When the Beecher-Tilton affair was revealed, she was relentlessly attacked by her family for supporting Woodhull instead of her brother.

Even years before the scandal came out, there were subtle hints about the affair. In a letter from Isabella Beecher Hooker to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, likely written in 1869, Beecher Hooker says that both Elizabeth Tilton and Henry Ward Beecher claimed that Stanton was a supporter of free love. Beecher Hooker asks whether that is true. Remarkably, both Tilton and Beecher are mentioned in the same letter asking about Stanton’s thoughts on a subject that would soon be used to slander the suffrage movement.

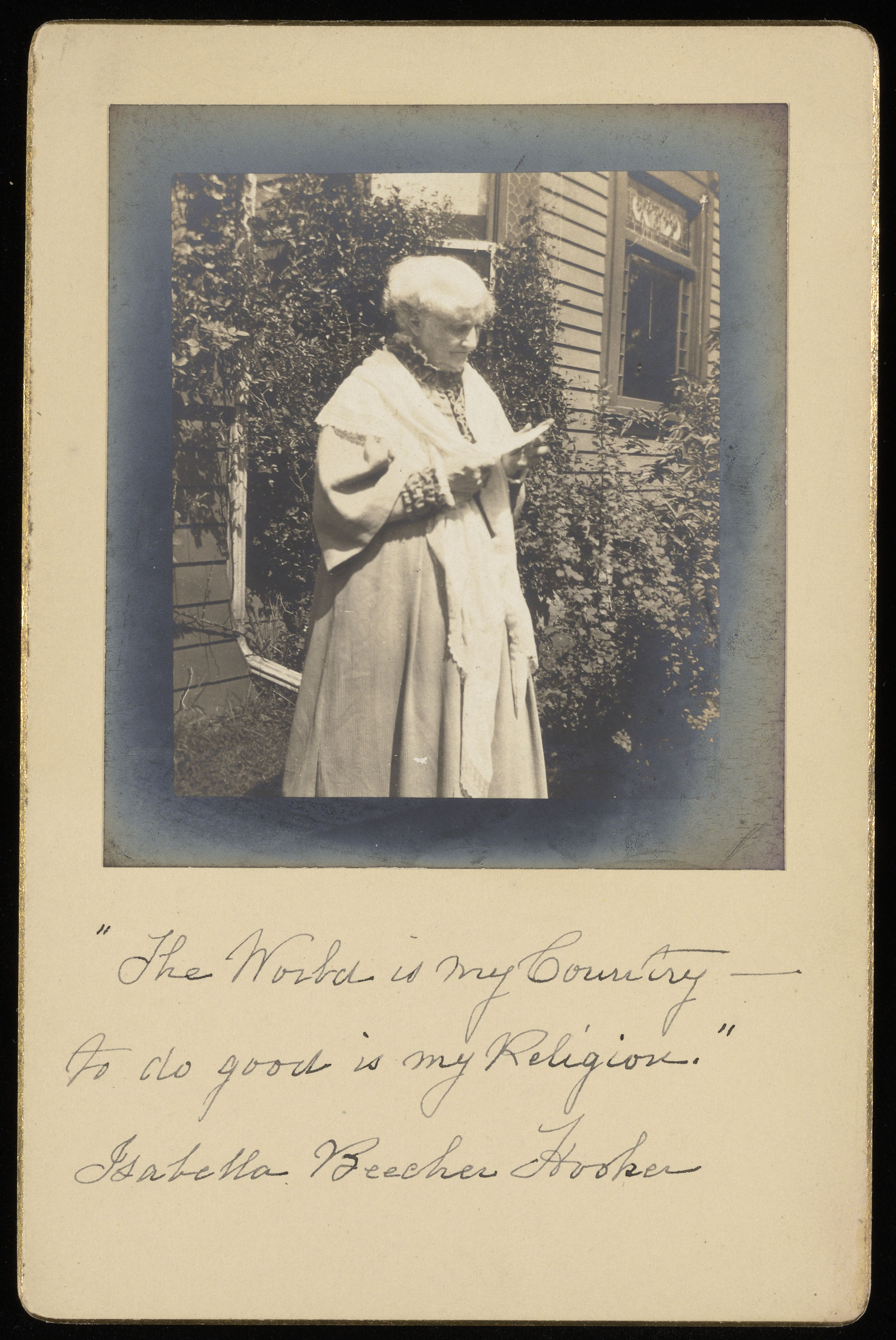

Isabella Beecher Hooker writes to her husband telling him that the Beecher-Tilton scandal came out in the newspapers.

On November 3, 1872, Isabella Beecher Hooker writes her husband that the scandal has finally been picked up by the major news outlets.

“The blow has fallen & I am so thankful that we all are prepared for it in some measure….The main facts accord with what I have heard from Mrs. Stanton & Susan--but there are dreadful particulars which may be fake or exaggerations--still even these seem probable to me….I find when I can talk over all my thoughts--hopes, fears, everything[,] with an outsider it is a real help--but this has not availed to relieve my mind of a single apprehension as to the ^very^ truth of the statement.”

The tension between Beecher Hooker and the rest of her family is already starting to come to light, as she believes that the facts of the case do not support her brother’s innocence. Throughout the scandal, women bore the brunt of the blame. Four days later, on November 7, 1872, Beecher Hooker receives a letter from her friend Hannah Comstock complaining about the inequitable treatment of women.

“I feel much for your brother, but if these charges are true & he attempts to escape under Mrs. Woodhull's skirts[,] all the more dreadful his fall will be in the end….I am ready for work on this great social question & care but little what is said if I may only see & do my duty. As it was in the day of Adam, the woman who had done the wrong, so now in this last day the woman must bear the blame.” In a letter also dated November 7, 1872, Susan B. Anthony writes that the women wrapped up in the scandal disproportionately bore the blame, saying that people “may expose the murderer--the thief--the [faker?]--every possible offender & offense except man’s violation of of [sic] the social code!! how is that for purity?”

The scandal did not die down quickly. In the following years there were trials, an excommunication and continuing newspaper coverage. On September 3rd, 1874, Isabella Beecher Hooker complains to her husband, John Hooker, about the treatment of Victoria Woodhull.

“There is one thing in the defense that gives me great pain--the characterization of Mrs. Woodhull---if she was a human hyena for publishing what she had every reason to ^believe to^ be true, & what a great part of the American people have since been compelled to accept as substantially true, & if the destitution of her business by government seizure & weeks in jail were ^a^ legitimate penalty for her offense, what of the women whose lips framed the lie & thrust it into unwilling ears & sealed it by months & years of silence.”

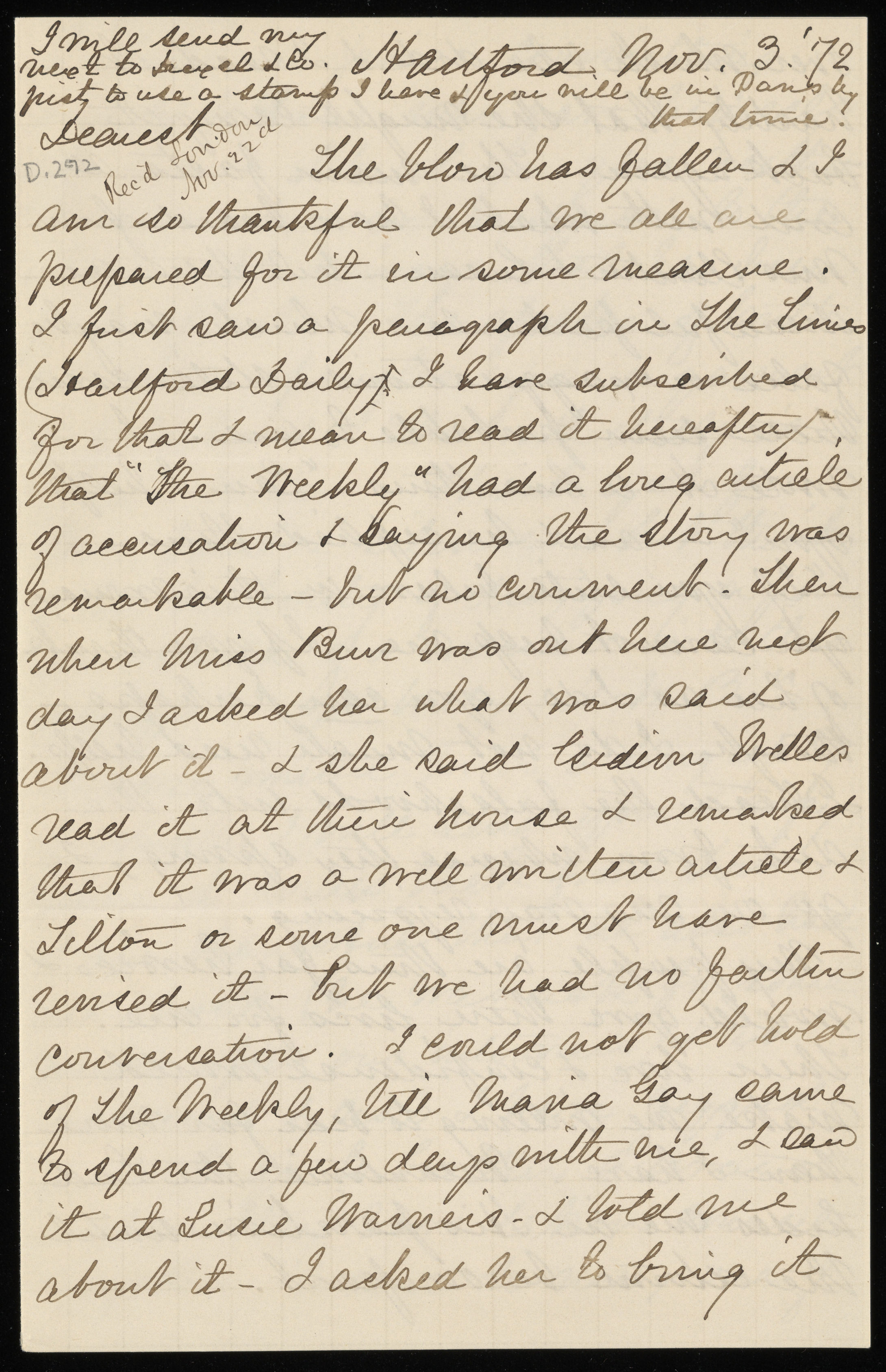

Olympia Brown complains to Isabella Beecher Hooker that she is neglecting her suffrage work.

The Beecher-Tilton scandal affected the suffrage movement not only by the bad publicity it brought but also by temporarily decreasing Beecher Hooker’s involvement in the movement. In an angry letter one year after the affair was exposed, Olympia Brown complains to Beecher Hooker that she was not helping plan a suffrage meeting.

“[A]s to casting all the responsibility of getting up the meeting on me[,] it is absurd....now if there is any meeting at New Haven it is evident that you will just have to put your hand to the work….you say your brothers [sic] affairs weigh heavily. Now take my advice[,] just let your brothers [sic] affairs rest and attend to this meeting[,] our cause is more important than ten thousand Beechers[,] besides you can do nothing about his affairs[,] he must work out his own salvation or condemnation & we must do likewise & we had better begin it by making this N.[ew] H.[aven] meeting a success.”

This letter is one of the most heated letters in the collection. Not only does this offer a window into the conflicts within the suffrage movement, but it also demonstrates the impact that the scandal had on Beecher Hooker’s life. The scandal would continue to shape her life for years to come.

The scandal generated significant tension between Beecher Hooker and her family. From the beginning, she was criticized for disloyalty because she did not automatically believe in Henry Ward Beecher’s innocence. In a letter from November 9, 1872, a few days after the scandal was publicized in the mainstream newspapers, Henry Ward Beecher himself tells his sister “[Y]ou take too devious a view. At present, you will help me most, as will all my family friends, by a calm silence.” As the scandal progressed and Beecher Hooker’s views on her brother became more publicly known, she would fall under further scrutiny by her family.

In a letter to her husband written on September 3, 1874, Beecher Hooker complains that Henry Ward Beecher is angry that she thought he was guilty. “I cannot yet see why he should have heated me as he has--I who would have been willing to be accursed of all men for his sake if so be he might be honest & true to his own connections.” Beecher Hooker’s persistent pressure on her brother to confess angered her family.

On September 23, 1874, Elizabeth Cady Stanton writes to John Hooker expressing her outrage about a public attack on Beecher Hooker by her brothers. Stanton also touches on the rumor circulating at the time that a group of suffragist “free lovers” tricked Beecher into having the affair.

“You 2 read with shame for the men of our day. These outrageously [sic] attacks on your noble wife: & brought all too by the baseness of her own brothers!!...Do you note Mrs. Stowes [sic] letter in today’s Tribune, with such astonishing proof of her brothers ‘crime’ what folly to speak of him as the innocent victim of a circle of ‘free lovers.’”

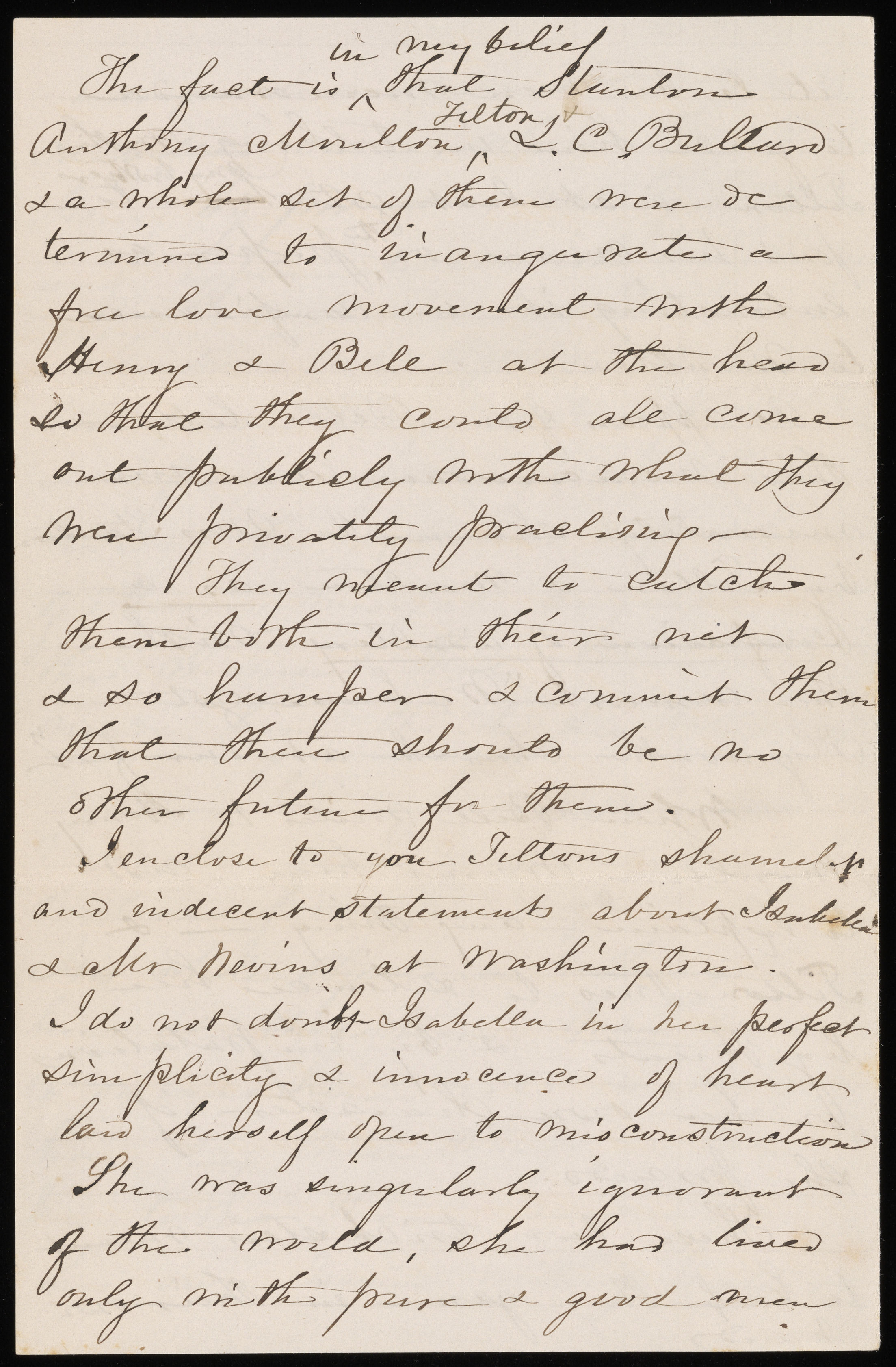

Harriet Beecher Stowe writes to John Hooker about her belief that many suffragists are “free lovers.”

Harriet Beecher Stowe, Isabella Beecher Hooker’s half-sister and the author of the famous abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, was one of the family members who criticized Beecher Hooker. A letter she writes in September 1874 to John Hooker shows the immense amount of pressure Isabella Beecher Hooker was under to declare her brother innocent.

“The fact is ^in my belief^ that Stanton[,] Anthony[,] Moulton[,] Tilton[,] L.C. Bullard & a whole set of them were determined to inaugurate a free love movement with Henry & Bell [Beecher Hooker’s nickname] at the head so that they could all come out publicly with what they were privately practicing... It is a question on which side you ^& Bell^ are to be found? All your friends & Bells [sic] friends long for a reconciliation and a restoration of old love...Why do can not you & Bell come out & say ‘I have been cruelly deceived, I have had false evidence presented & been denied explanation & this led to actions that I now regret.’ Let her say that [stricken: illegible] now she has been permitted to see the truth she gladly believes in her brother’s purity.”

Beecher Stowe’s letter again illustrates the pressure Beecher Hooker was under to say her brother was not guilty. Beecher Hooker’s family even put out a public statement saying that she was mentally ill to account for her refusal to believe her brother innocent. This statement is directly addressed in Beecher Stowe’s letter to John Hooker: “I observe in your letter you appear much hurt about that statement ^about Bell.^” Eventually, Henry Ward Beecher’s family was successful in rallying most of his friends to support him, and Henry Ward Beecher’s reputation survived the scandal.

Isabella Beecher Hooker was not the only person to be pressured to support Henry Ward Beecher. In a letter from Elizabeth Cady Stanton to John Hooker on January 8th, 1875, she refuses to admit that Elizabeth Tilton’s confession was a fabrication and says that “If Mr. Beecher’s innocence demands the sacrifice of the veracity & honor of the noblest women in the country it is purchased at too great a cost & I for one shall not be silent.”

By March of 1876, the Beecher-Tilton scandal had started to fade from public memory. Ultimately, at significant personal cost, Isabella Beecher Hooker and her husband stood by their principles and resisted the pressure to declare Henry Ward Beecher innocent. The only person who escaped the scandal mostly unscathed was Henry Ward Beecher himself, who was able to remain a preacher in his church and was never convicted of adultery.[5] Tilton’s reputation was tarnished and Woodhull’s business was destroyed.

After the court trials were concluded, John Hooker, the husband of Isabella Beecher Hooker, took a final opportunity to compile his conversations with some of the most important actors in the Beecher-Tilton scandal. At the conclusion of this document, he writes:

“My whole object was to have cleared up if possible the difficulties growing out of facts known privately to my wife & myself….I felt that these secret facts unexplained compelled me to believe him [Henry Ward Beecher] guilty. I felt like one who possess the secret of a murder & sees a trial going on in which the secret facts known to him are beyond the reach of the public prosecutor. I felt as though if the jury should unanimously acquit him upon the evidence laid before them & the public confirm it by acclamation, I should yet always have to think him probably guilty.”

The Isabella Beecher Hooker Collection contains a rich array of letters and related materials covering a wide range of topics from daily life to the suffrage movement. While the Beecher-Tilton scandal is a lesser-known event now, it had a large impact on society at the time. It captivated the public nationwide for several years, damaged the reputation of the suffrage movement and led to the passage of anti-obscentity legislation, damaging efforts to promote birth control. Reading these letters illuminates the different perspectives of those caught up in the event and the impact on their lives, both personal and public.

Bibliography

DuBois, Ellen Carol. Suffrage. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020.

“Isabella Beecher Hooker and John Hooker Papers.” River Campus Libraries. University of Rochester. Accessed July 7, 2020. https://rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/Isabella-Beecher-Hooker-Papers.

“People & Ideas: Henry Ward Beecher.” PBS. Accessed July 18, 2020. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/godinamerica/people/henry-ward-beecher.html.

Shaplen, Robert. “The Beecher-Tilton Affair.” The New Yorker, June 5, 1954. Accessed July 11, 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1954/06/12/the-beecher-tilton-case-ii.

[1] “People & Ideas: Henry Ward Beecher,” PBS, Accessed July 18, 2020, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/godinamerica/people/henry-ward-beecher.html.

[2] Ellen Carol Dubois, Suffrage (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020), 92-95.

[3] Dubois, Suffrage, 93-94.

[4] “Isabella Beecher Hooker and John Hooker Papers,” River Campus Libraries, University of Rochester, Accessed July 7, 2020, https://rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/Isabella-Beecher-Hooker-Papers.

[5] Robert Shaplen, “The Beecher-Tilton Affair,” The New Yorker, June 5, 1954, Accessed July 11, 2020, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1954/06/12/the-beecher-tilton-case-ii.