“Bully rebles in sight”: A Rochesterian in the Civil War

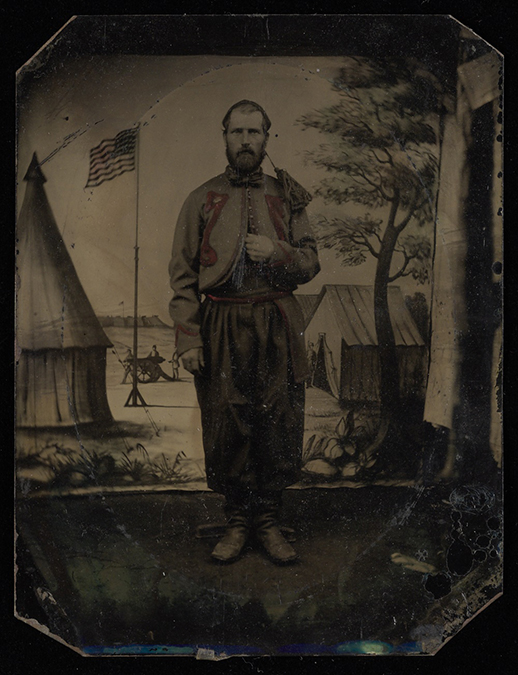

Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation (RBSCP) recently received a donation that shines a light on one Rochester man’s experiences fighting in the American Civil War. Dr. Julie Brown, her brothers Peter and Robert McGraw, and cousin Ted McGraw donated their great-grandfather John McGraw’s letters. McGraw was a private in Company E of the 140th NY Volunteer Infantry between September 1863 and March 1865. In addition to over 60 letters written by McGraw, the collection contains a glorious, hand-colored tintype of McGraw in his Zouave uniform. Zouave regiments in the US Civil War were based on French North African army units who wore flamboyant uniforms. In 1863 and 1864, three Union regiments, including the 140th New York, were issued with Zouave uniforms. McGraw had his photo taken in uniform in March, 1864.

The letters begin in Elmira, NY, where he was briefly stationed before heading south. They continue from eight different locations in Virginia. After being wounded in the shoulder, McGraw continued to write from hospitals in Washington, D.C., Maryland, and Philadelphia before being discharged in the spring of 1865. All of the letter are written to his wife Mary at the family home on Reynolds Street in Rochester’s 8th ward. John and Mary came from Irish families that immigrated to Rochester via Canada. The men in both families worked as masons and stonecutters and found work on the construction of the Erie Canal. The letters provide information about the movements and engagements of the 140th, but they are also valuable for the insight they provide into John McGraw’s hopes and fears during the war. He is open about his homesickness and the miserable conditions he and his fellow soldiers suffer from.

At the start of the war, John and Mary have a young daughter and son, with another son born to them a month after John enlists. He asks about his family throughout the letters, often closing by sending his love to the children and other family members, especially his father, who he refers to as “the old man”. In July, 1864 John and Mary’s son Willie dies and two months later baby Johnny dies as well. After hearing of Willie’s death, he writes to Mary “l receive your letter and was sorry to hear of poor Willes Death but l hope he is happy in heaven you mentioned in you letter that l would rether see him dead then live to go through as much as l have well l would rather see him dead then go through one half as much…”.

One theme running throughout the letters is John’s complaint that Mary does not write him frequently enough. While we have over 60 letters from John to Mary, her letters to him do not survive, possibly because of camp conditions and the fact that he was frequently on the move. An August 1864 letter from John reads “l Wich you would Answer my letters more reaugler than you do l received one letter in three weeks from you”. However, at the time of this letter, Willie McGraw had just died and baby Johnny was sick; Mary must have had her hands full at home.

Another theme in the letters is the food McGraw is served. From an initial meal in Elmira of “mush and milk” to a feast in Baltimore’s Garvis Hospital consisting of “butter fresh meat and salt meat and ham and Beets cabbage and turnips and Bred pudding and all the Bread we can eat”, McGraw consistently writes about the misery of hunger, treats he receives, and missing the food of home.

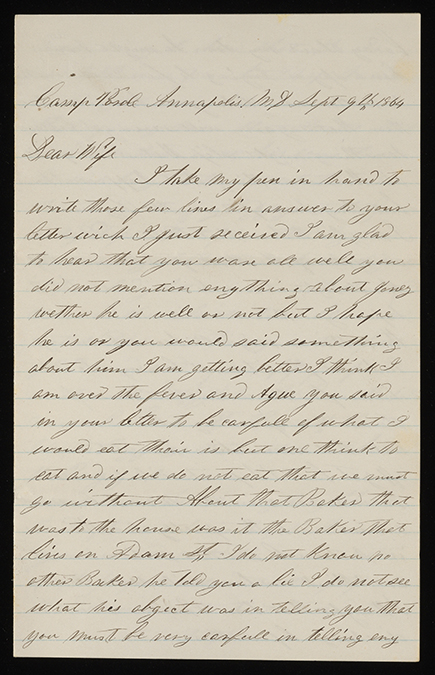

John McGraw’s spelling and grammar are often non-standard, but his penmanship is very precise. The letters are surprising easy to read considering they were written in tents, fields, and hospitals. The collection also contains transcriptions of the letters, which makes them even more accessible. The collection is fully processed and is open to researchers. The finding aid is available here.

Add new comment