Lola Haskins’s Take on the Pastoral: How the Female Voice Both Disassembles and Constructs Fantasy

Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation (RBSCP) is celebrating National Poetry Month in April by highlighting their collections on poetry and publishing houses, one of which is the papers of BOA Editions Limited. Founded in Rochester in 1976 by poet, editor, and translator Al Poulin, BOA is a non-profit publishing house that has published over 300 titles of poetry, poetry-in-translation, and short fiction. The collection spans from 1996 to 2014 and features numerous poets’ manuscripts, correspondence, photographs, and ephemera.

In June 2004, BOA published Desire Lines, a collected works of new and selected poems by poet Lola Haskins. Haskins, now 75, is an accomplished pianist and former professor of computer science at University of Florida. She has received numerous fellowships and awards for her poetry, such as the 1995 Emily Dickinson/Writer Magazine award from Poetry Society of America. When reading through the work of dozens of poets currently housed in the BOA collection, Haskins’ Desire Lines struck me; I found the voices in her poetry particularly jarring and fitting for this time of the year.

With spring slowly making its entrance in Rochester, Haskins’ web of pastoral scenes conjure images of farmland in warm-weathered seasons. While Haskins is an expert scene-maker, she also gives voice to many female figures in her poems, often placing them in the middle of the agrarian landscape. Yet, the idyllic, comforting scene of the pasture is laden with something of great contrast, something not quite nameable but felt prominently in the poem’s undertones. For example, I have grown plump and settled these months begins with the speaker introducing the routine of her “domestic” life.

I have grown plump and settled these months

I have grown plump and settled these months,

domestic as the white chickens that peck

outside, whose smooth eggs our children

gather in baskets. Yet I must tell you

what I have learned. Inside each egg

is a yellow scream. At night sometimes,

when all the chickens are asleep under

the moon, the eggs shriek in their shells,

wanting something. When I come

from my bed and pick them up,

they quiet, as I rock them in my skirt.

By the middle of the stanza, Haskins distorts our expectation of a pastoral fantasy with the line, “Inside each egg / is a yellow scream.” The realism of the first half of the poem is overridden by the dream-like confession that follows. The speaker seems to be directing this knowledge to not only the reader on the outside of the poem, but inside the world of the poem itself. She seems to be speaking to a presumed male figure; the other half of the “our children,” and the “you,” that the speaker “must tell” what she has learned. The domestic woman with introspective edge reappears in Haskins’ 1993 poem, “Farm Wife,” where, again, the entrance of a male figure subtly makes its way into the middle of the poem, with the line “The swoony glide of his knife / spreading butter.” This is the only male pronoun mentioned in the poem, the others being distinctly female throughout. There’s also something quite dreamlike in the poem as the reader is led from one image to the next, creating a fantasy world of images that span from “red geraniums” to the “dance / of Paris, in France.” The journey from image to image is rich, no matter the brevity of the lines themselves.

Farm Wife

She tends the red geraniums.

When their clustered eyes go dark,

she cuts them from their stems.

With her thumb she strokes the

furry leaves, not like common cloth

but the nap and shift of velvet

falling heavy over her hips,

the long slow dance

of Paris, in France.

The swoony glide of his knife

spreading butter.

Not the bread it takes her

all day to bake,

the coarse knead and punch,

but the rise,

the pale cheek of flour,

the dip and shimmer of the heat,

the arched backs of the hills

in their arms of sky.

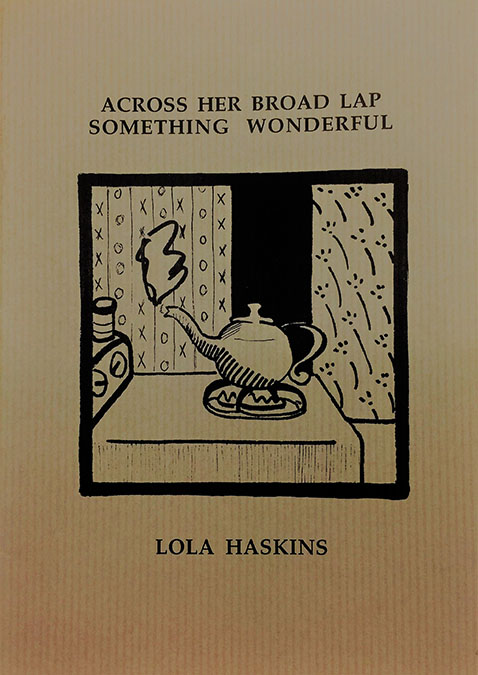

Inanimate pastoral objects are given life in many of Haskins’ poems. The eggs shriek in the first poem, the hills arch their backs in the second, and the clothes in “Things” from Haskins’ 1989 publication, Across Her Broad Lap Something Wonderful, seem to hold agency over their “spreading” and “weaving themselves” in and around the stream they are being washed in. There are more end-stops in this poem, creating definite pauses and clear assertions that allows the reader to follow the abstraction found in the agency of inanimate objects.

Things

A telephone is ringing in the field.

The cattle circle it,

wondering if it will feed them.

When they graze away,

they leave a ring of flat seed-heads

in the high wheat.

In the river, clothes are washing.

They rub against the rocks.

Sheets are weaving themselves

in and out of the current.

A red dress billows downstream.

A done shirt is spreading its sleeves

on a blueberry bush.

In the house, the kettle is boiling.

Little steamy breaths huff over

the stove ‘til all the water’s

gone. Then, slowly, the bottom

burns through. First red, then white,

then, through a rust-edged hole,

the first blue flame inside.

The tensions embedded in Haskins’ poetry are beautiful, evoking something thoughtful about the relationships she often creates between the speaker of the poem and the objects. Each of these poems are featured in Haskins’ Desire Lines. For more information on RBSCP’s BOA collection, visit https://rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/sites/default/files/atoms/files/BOA-Editions-Limited.pdf.