Imagining Alexander the Great

Lately I’ve been fascinated by Alexander the Great. Or should I say, adaptations and appropriations of Alexander, which are still on-going. In the past year I’ve encountered Alexander in unexpected places. I’ve watched him streaming on Netflix as the enormous, red-haired, oxen-driving hero Iskandar, resurrected to fight for the Holy Grail in the Fate/Zero anime. I also started reading the Budge translation of the Ethiopian Alexander Romance, in which the titular hero is Christianized (not unusual for Alexander Romances of the medieval period) but his form of praying is distinctly Muslim, which speaks to the Arabic source material of this version of the wildly widespread medieval romance. Alexander seems to be this weird, mutable figure that people can adopt for their own cultural purposes.

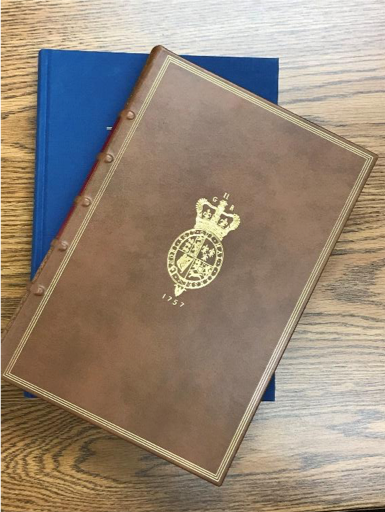

In thinking about these sort of cultural uses of real historical figures, I was reminded of an especially beautiful facsimile the Robbins Library possesses of Royal MS 20 B. xx, a manuscript of the French prose Alexander Romance that was created in Paris in the 1420s. The facsimile reproduces not only the interior of the manuscript but attempts to recreate the overall experience of reading the manuscript by reproducing the binding as well. For those of us without ready means of travelling to see the real thing, this is a handy substitute.

The current binding is not original to the manuscript but was an 18th century addition. The facsimile also replicates some of the front matter, which indicates that this manuscript was held in the royal collection. According to Joanna Fronska in the critical matter accompanying the facsimile, the first known owner was Henry VIII (Facsimile Edition 306).

This facsimile is also fully colored, so readers can have a sense of the real color of the pages—not white—and fully appreciate the 86 miniatures spread throughout the romance. The facsimile even replicates the gold leaf so that there is a genuine metallic shine as you page through.

To go back to my earlier point about appropriations of Alexander, one of the things I find most interesting about this manuscript is how the past is re-imaged in order to represent the expectations of 15th century readers. It is common practice in manuscript illuminations to depict figures of the past within contemporary settings and clothing. On a practical side, this can help readers quickly identify figures within an illumination. Take Olympias, Alexander’s mother, for example:

Here on fol 7v, Olympias is recognizable as a queen without even needing to understand the surrounding text: Olympias is seated in the center of her attending ladies. The ladies all wear fifteenth century attire. Both close-fitting long sleeves, like those worn by the queen, and wide, elaborately-lined sleeves were common in French manuscripts of this time period (Gathercole 46-8). The bright colors and contrasting sleeves are typical of images of the nobility (65). Ladies also generally wore veils, often white, over their hair. Veils could be a variety of shapes, even “held up by pins and have a winged effect…headveils could even be worn by queens underneath crowns” (18). Olympias herself is clearly identifiable as a queen due to her throne, crown, and ermine cloak, a covering that only nobility are allowed to wear. Olympias’ depiction as a medieval queen is present even when she is ill (Fol. 27r). Apparently, even when you are sick, naked, and in bed, if you’re a queen, you better wear your crown.

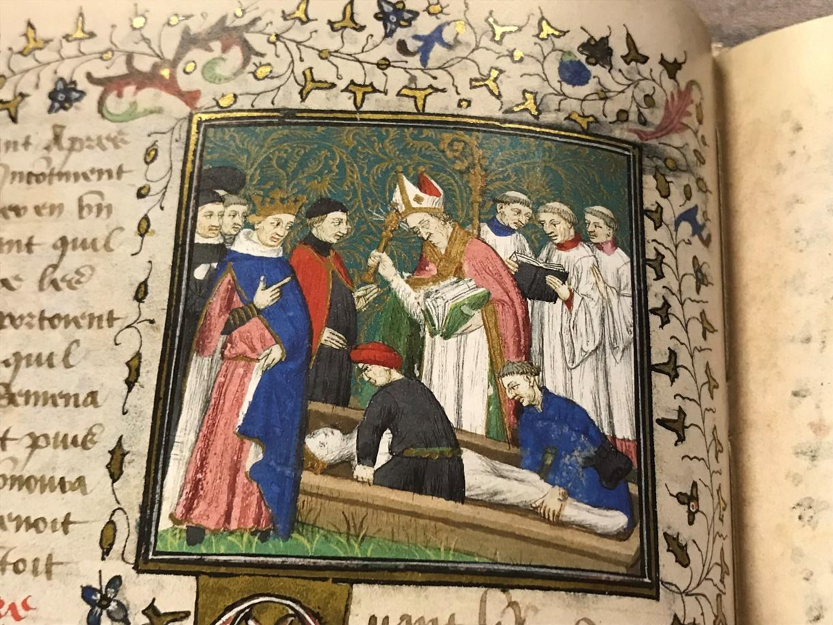

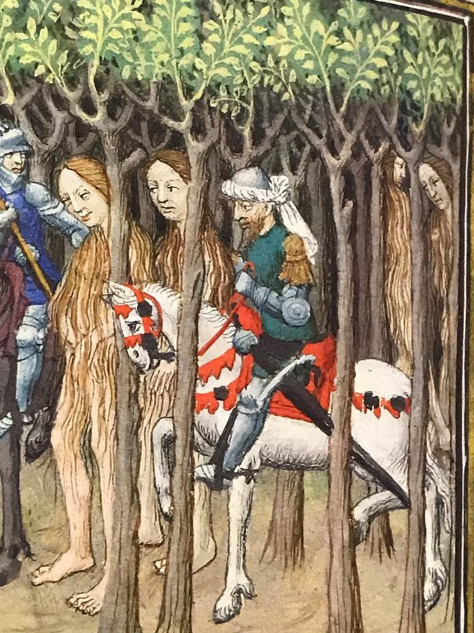

This anachronistic depiction of characters is consistent throughout the manuscript. The Amazons, legendary warrior-women from Greek mythology, are neither armed nor armored (Fol. 47v). Nor are they particularly Greek. Instead, they closely resemble Olympias’ ladies pictured above.

The queen is marked by her crown and gown. This lack of armament is conspicuous beside Alexander’s army and their military outfitting. They have mail, swords, and halberds, juxtaposed to the non-martial bearing the of the Amazons. It is worth noting, however, that the medieval anachronism is consistent for either group; his army is presented in medieval armor and surcoats, with medieval weaponry.

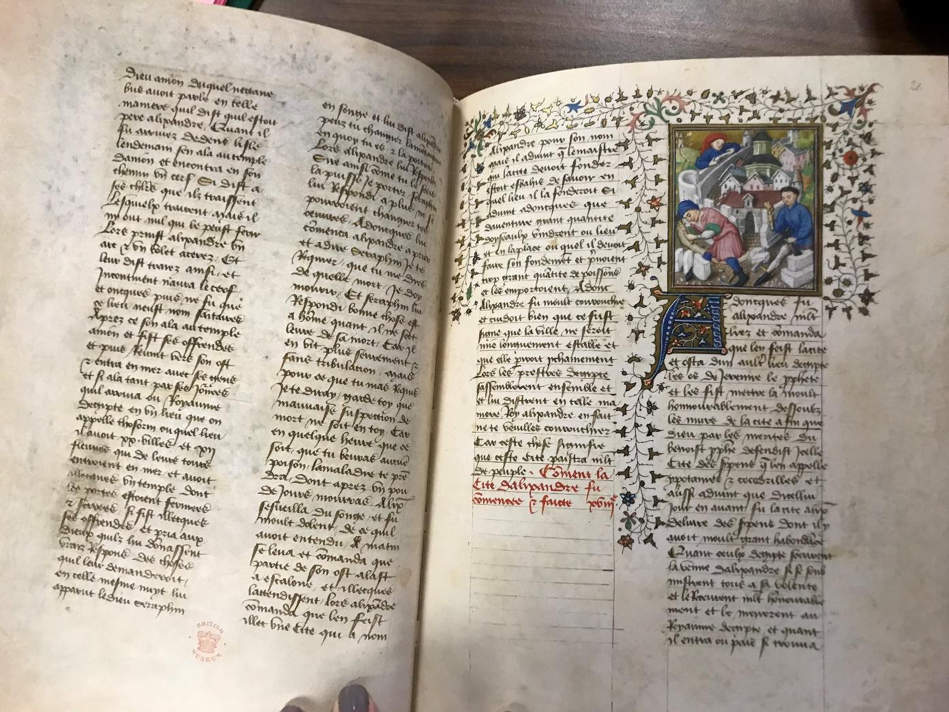

Funeral scenes are also Christianized. At King Darius’ funeral, pictured below (Fol. 38v), a Christian priest officiates. The priest appears to be high-ranking, judging by his miter and rich robes. He is likely reading The Office of the Dead, and behind him to the right are three monks, easily distinguishable by their tonsures. Alexander is in the foreground of the image, crowned.

There is a practical purpose to these anachronisms, of course. Incorporating contemporary cultural visual cues and symbols into manuscript illumination allows readers to instantly recognize key figures and important events. In turn, these sorts of illuminations can improve a reader’s navigation of the text, since they are often used as chapter markers. However, it can also be interesting to think about the sort of cultural work that is being done through these types of illustrations. Alexander is a pre-Christian figure, so what does it suggest when he participates in what is a clearly Christian rite? Why would a French manuscript depict a non-European, pre-medieval king known for conquering large eastern territories as European, medieval, and Christian? One possible answer is that these illustrations reflect a Eurocentric worldview and fantasies about conquering these eastern territories as Alexander once did.

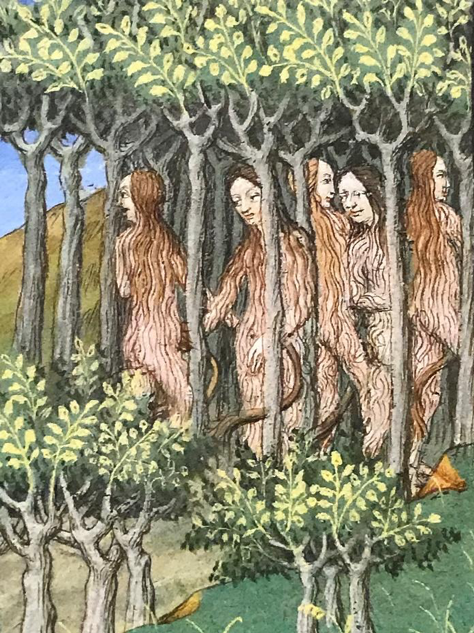

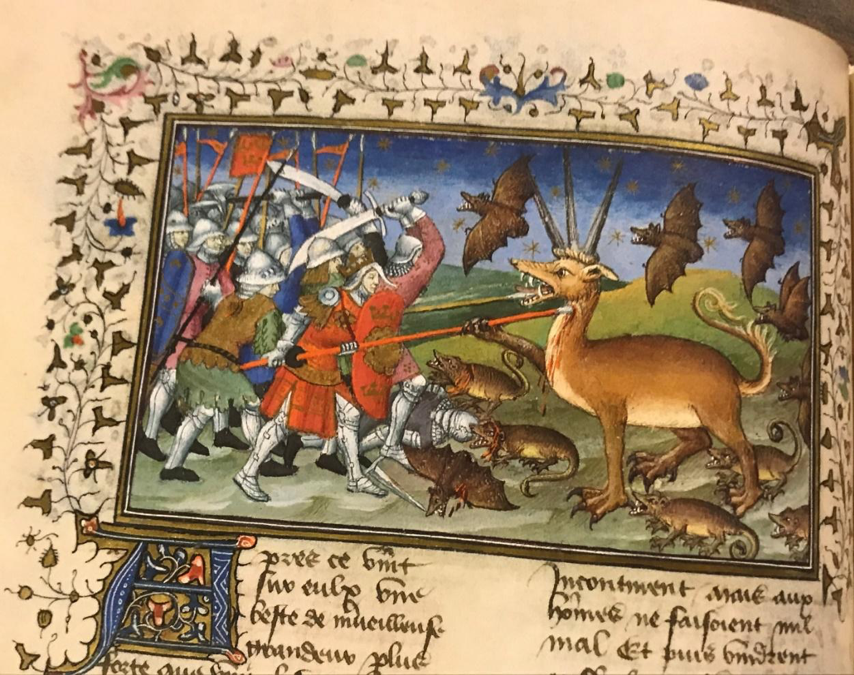

But to end on a slightly lighter note, let’s look at some lady-monsters.

The Alexander manuscripts are famous for their depictions of marvelous creatures who blur the lines between man and beast. The women with ox-tails are delightfully furry, with tails clearly depicted (left image, Fol. 58r), and the 7-foot-tall women are as large as Alexander and his men on horseback, though they are sadly missing their hoofed feet (Fol. 58v). These giant women are described in the romance as extremely beautiful despite their unusual height.

Also, this guy:

According to Maud Pérez-Simon, he’s an Odontotyrannus, which means “colossal animal with huge tusks” (Facsimile Edition 277). And for the name alone you should look at this book. He is the world’s angriest deer. He has 3 horns and fangs. And an army of bats and mice. What’s not to like?

Spending an hour or so contemplating the beautiful construction of this facsimile isn’t a bad way to spend an afternoon. Additionally, the accompanying book translates the entire text, so you can read the romance—or select pieces of it—even if you can’t read Old French.

Works Cited:

Gathercole, Patricia M. The Depiction of Clothing in French Medieval Manuscripts. The Edwin Mellen Press, 2008.

The Romance of Alexander: Royal MS 20 B. xx Facsimile Edition. 2 vols. Edited by Joanna Fronska, Maud Pérez-Simon, and Siegbert Himmelsbach. Quaternio Vernag Luzern, 2014.

Add new comment