A Look into the City of Rochester's Past

As a former student of Religion & Classics professor Dr. Margarita Guillory, I became her research assistant in spring of 2018 to gather information for a project called "Digitizing Rochester Religions." My task was to read and summarize material from the Dr. Walter Cooper papers, box 4, folders 1-19, in Rare Books & Special Collections Library by creating an annotated bibliography. The blog post is a summation of major themes from the papers and personal experiences with Civil Rights leaders Dr. Walter Cooper and Constance Mitchell.

The Dr. Walter Cooper papers contains newspaper articles, documents, and essays from the 1950s and 1960s on housing discrimination, black Muslims, police brutality, and the 1964 race riot in Rochester, NY. The black community faced violations of human rights, police brutality, housing, and employment discrimination. With the influx of thousands of black families from southern states to Rochester, the city was not structurally or institutionally prepared to house and integrate these families into city living. As a result, black families lived in two historically black neighborhoods: Corn Hill and Group 14621, formerly known as the Baden-Ormond neighborhood. Many properties in these neighborhoods were in poor condition prior to new families moving in. Companies such as Eastman Kodak, Bausch & Lomb, and Xerox, did not readily employ blacks because they lacked education and technical skills. Middle-class people of color received the "full weight" of discrimination because their finances, professional attainments and social skills “count[ed] for little against [their] black skin;” whereas less wealthy people of color were more easily confined to slums because of finances.[1] When black families were able to purchase nice homes, they experienced aggression from white neighbors. For example, Walter Jones purchased his home in a predominantly white neighborhood in 1962.[2] Shortly after moving in, Jones reported the gas pipe in his home was disconnected. Neighbors claimed he was welcomed to the neighborhood, and said vandalism occurred to other properties before he moved in. Black homeowners also had to prove themselves in order to defy racial stereotypes. According to Desmond Stone and Germond Jack, an unnamed, middle-class black man trimmed his bushes and painted his house on the second day after moving in.[3] He did so to prove he cared about his home and would not depreciate property value. These ails were just some of the causes for the 1964 race riot.

The black Muslim population in Rochester began to increase in the 1950s due to police brutality and visits from an influential black Muslim named Malcolm X. Originally called the Temple of Islam, Wallace Fard Muhammad founded the Nation of Islam (NOI) and taught Elijah Poole his teachings in 1931.[4] When Fard disappeared in 1934, Elijah Poole became known as Elijah Muhammad and continued to expand the NOI by establishing temples all over the United States. A major principle of the NOI is black social, economic, and institutional separation from white establishments.[5] The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) denounced Elijah Muhammad’s separatist philosophies, and firmly articulated their belief in integration to newspapers throughout the 1960s.[6] Police officers, government officials, and other power structures felt threatened by black Muslims because their anti-integration philosophies influenced frustrated and militant black communities nationwide. Muhammad mentored Malcolm X and taught him philosophies of the NOI. Malcolm X became Muhammad's right hand man and a minister of Temple No. 7 in Harlem, NY.[7] Malcolm X frequently made trips to Rochester to condemn police brutality and the imprisonment of black Muslims. In February 1963, Malcolm X led two-hundred citizens across Manhattan in protest of the arrest of black Muslims in Rochester. (See box 4, folder 6 for more information).

Dr. Walter Cooper and Constance Mitchell had a relationship with Malcolm X. Constance Mitchell was a local Civil Rights activist in Rochester, NY, and served on the Board of Monroe County Supervisors. According to the interview with Dr. Cooper, Mitchell’s former address, 36 Greg Street, was the meeting place for dignitaries to talk about pressing social issues. In a Democrat & Chronicle article from November 22, 1992, Dr. Cooper stated Malcolm X used to call him “Big Coop” and he called Malcolm X “Big Red.”[8] Although Dr. Cooper was not a Muslim himself, he believed Malcolm X respected him because of his involvement with the NAACP. According to Mitchell, Malcolm X frequently came to her house for question and answer sessions that revealed predictions about the future of the black community. On February 4 2017, Mitchell was awarded the Frederick Douglass metal for her accomplishments in the city of Rochester at the Susan B. Anthony Center’s Legacy Award Ceremony, where I had the honor of meeting her.

Although Rochester had an active Civil Rights presence in the 1960s, police officers continued to harass and racially profile black residents. One case is from Dr. Cooper himself. According to Dr. Cooper, an officer pulled him over because he looked “suspicious.”[9] Dr. Cooper pointed out he was wearing a white collared shirt, a tie, and slacks. The officer said he thought Dr. Cooper was going to rob a school. Another altercation occurred between black Muslims and the police on January 6, 1963. On this day, police came to a Muslim meeting on 304 North Street because they received a “man with a gun” phone call.[10] When police arrived, the guards refused to let police in. When police finally got inside the building, two black Muslims named Goldstein Small, and Donell Oliver, assaulted officers Anthony D’Angelo and John Hunt. D’Angelo and Hunt claimed several Muslims assaulted them, but only Small and Oliver were identified. The arrests reached Malcolm X and other black Muslims, who in turn, led a mass meeting in Harlem, NY to denounce the Rochester Police Department. Another case was from a man named A.C. White. On January 26, 1963, A.C. White was pulled over for driving while intoxicated.[11] According to White, the police officers hit him in the forehead with "billie clubs" before placing him inside the car, and then continued to assault him once they arrived at police headquarters. As a result of using excessive force, the police chief temporarily suspended the four officers with pay. These incidents sparked public outcry and further strained relations between the police and the black community.

In Dr. Walter Cooper’s essay titled Analysis of a Riot July 24-26, 1964, he argued discrimination, segregation, and mistreatment of black residents should have woken up the Rochester community. Mitchell stated she warned the city of a violent backlash, but no one listened. Dr. Cooper argued the main reasons the riot occurred is because Rochester experienced a rapid increase in population and did not have “absorptive power to accept and integrate newcomers into the institutional life of the community.”[12] The riot began on Friday, July 24, 1964 on Joseph Avenue and Nassau Street.[13] Police officers attempted to arrest a drunken man from the licensed street dance sponsored by the Nassau Street Mothers’ Improvement Association. The community objected to the arrest and became violent by throwing rocks at the police and destroying properties and stores. The riot continued on the next day in the Cornhill Neighborhood and more destruction of properties occurred. (See box 4, folder 17 for more information)

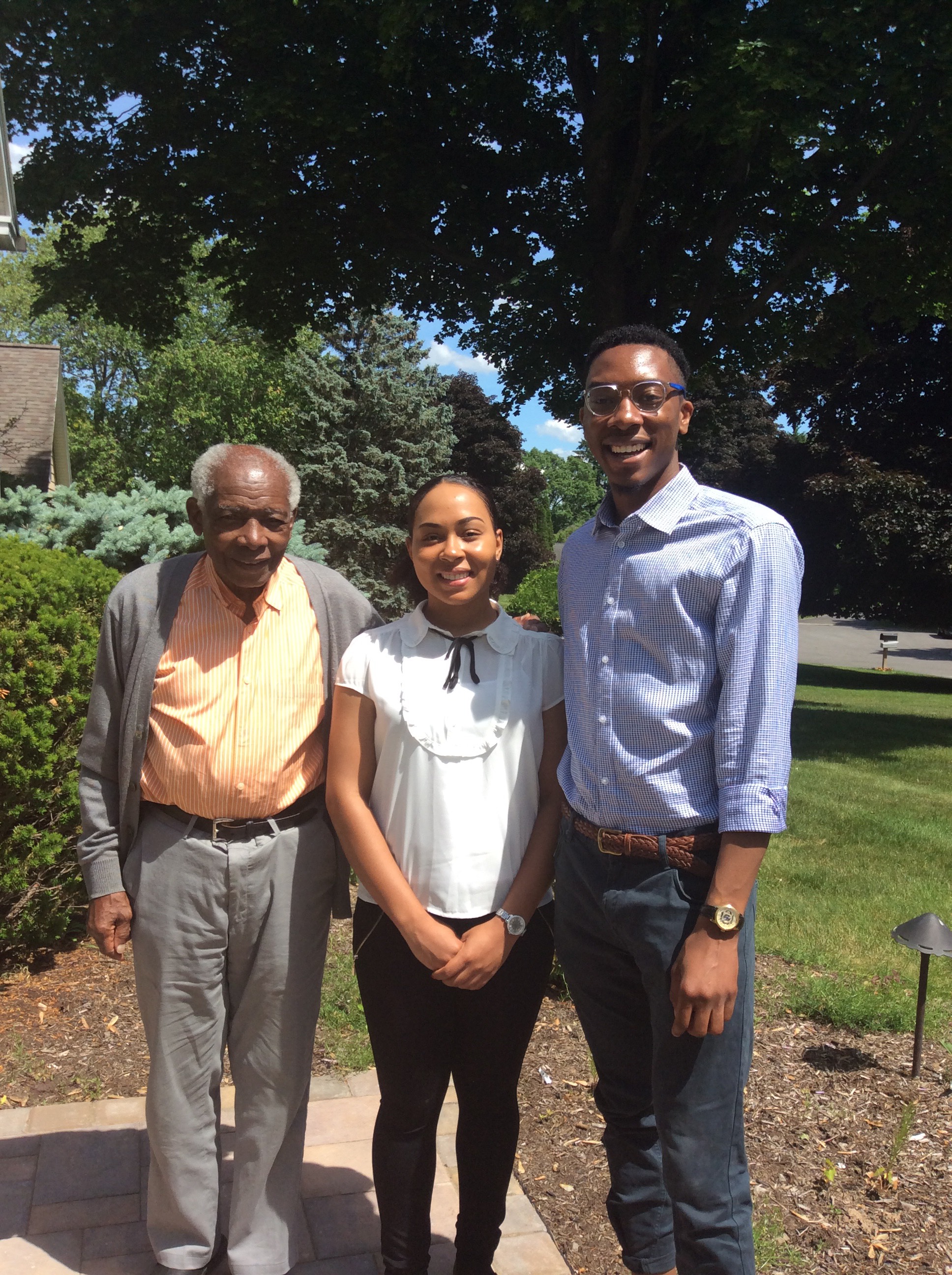

On June 12, 2018, I had the honor of interviewing Dr. Walter Cooper at his home in Penfield on the papers and his opinions on the current state of Rochester. The interview lasted about two hours and took place inside his living room. I was astonished at the accuracy and precision of his memory. Dr. Cooper recited names, dates, and events correctly whenever I asked him a question. I learned much from Dr. Cooper during this interview.

The Dr. Walter Cooper papers provided me with historical facts and information about the city of Rochester in the 1960s. As a child, I did not understand why certain parts of Rochester looked different from others; I thought that was just the way things were. It is sad to say sixty-four years after the riot, the neighborhood is still in shambles. There are well over forty vacant lots sprawling along Joseph Avenue. Take a walk down the avenue, walk into any of the corner stores, and you will find a lack of healthy food options, a plethora of tobacco products, and processed junk food. The neighborhood is in dire need of amenities community members need such as fresh produce, more grocery stores, parks, playgrounds, community gardens, bike lanes, and more. For outsiders, the neighborhood appears dangerous, but to me, it needs investment and revitalization. Social issues such as hunger, education, and jobs will be alleviated when the city of Rochester focuses on developing structures and resources in this part of the city.

[1] Stone, Desmond & Germond, Jack. “Housing Bias Hits Hard at Educated Negro: No Real Freedom of Choice Is Main Complaint” Dr. Walter Cooper Papers. Articles Prior to the Riots (1961 - 1963) box 4 folder 13. Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus LIbraries, University of Rochester.

[2] Vogler, William. “Gas Pipe Cut In Negro Home.” (November 1962). Dr. Walter Cooper Papers. Articles Prior to the Riots (1961 - 1963) box 4 folder 13. Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus LIbraries, University of Rochester.

[3] Stone, Desmond & Germond, Jack. “Negro Remains Man Apart In Community.” Rochester Times-Union. (June 10, 1960). Rochester Times-Union. Dr. Walter Cooper Papers. Articles Prior to the Riots (1961 - 1963) box 4 folder 13. Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus LIbraries, University of Rochester.

[4] Kihss, Peter. “In Return for Years of Slavery, For or Five States.” The New York TImes Book Review. (April 23, 1961). Dr. Walter Cooper Papers. Black Muslims Nationally, Articles (1951 - 1963), box 4 folder 4. Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus LIbraries, University of Rochester.

[5] Muhammad, Elijah. “Free Slave? - Free Master?” Muhammad Speaks. (January 7, 1961). Dr. Walter Cooper Papers. Box 4 folder 5. University of Rochester Libraries, Dept. of Rare Books and Special Collections, Rochester, NY.

[6] “NAACP Gives Stand on Muslim Sect.” Democrat & Chronicle. (February 22, 1963). Dr. Walter Cooper Papers. Black Muslims in Rochester, Articles 1963, box 4 folder 3. Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus LIbraries, University of Rochester.

[7] "Malcolm X: Biography." Biography.com. (April 2, 2014). Date accessed 8/1/18.

[8] New York Notes. “‘Big Red’ Was Here To Fight Brutality.” Albany, NY. (November 22, 1992). Dr. Walter Cooper Papers. Malcolm X (Articles from 1963 - 1992) box 4 folder 6. Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus LIbraries, University of Rochester.

[9] Blackwell, Jeffery. “Two Recall 1960s Civil Rights Struggles.” Democrat & Chronicle. (April 4, 2010). Dr. Walter Cooper Papers. Reflections on the Riots (1965 - 2002) box 4 folder 19. Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus LIbraries, University of Rochester.

[10] “Black Muslim, Police Clash; 2 Arrested.” Times-Union. (January 7, 1963). Dr. Walter Cooper Papers. Black Muslims Police Brutality Case (1963) box 4 folder 9.Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus LIbraries, University of Rochester.

[11] “Statement of Mr. A.C. White.” (February 5, 1963). Dr. Walter Cooper Papers. A.C. White Police Brutality Case (1963) box 4 folder 10. Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus LIbraries, University of Rochester.

[12] Cooper, Walter. “Analysis of a Riot July 24-26, 1964.” Dr. Walter Cooper Papers. Cooper’s Reflections on the Riot (1964?) box 4 folder 18. Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus LIbraries, University of Rochester.

[13] “Report.” United States Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation. (September 18, 1964). Washington, D.C. Dr. Walter Cooper Papers. Police Advisory Board Reflections: Official Statement on Riots and Community Protest of Board (1964 - 1965) box 4 folder 17. Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus LIbraries, University of Rochester.

Add new comment