Witch Cake 1: A Scottish Conundrum

Throughout the month of October 2017, the Robbins Library Instagram account highlighted the spookier aspects of our collection during the lead up to Halloween. Because a significant part of our collection is devoted to witchcraft and demonology throughout the ages, we created the hashtag #WitchcraftWednesday in order to help showcase some of our more, let’s say, unique items.

As I was looking into appropriately witch-y objects to photograph for #WitchcraftWednesday, I came across a term that I hadn’t ever seen before: witch cake.

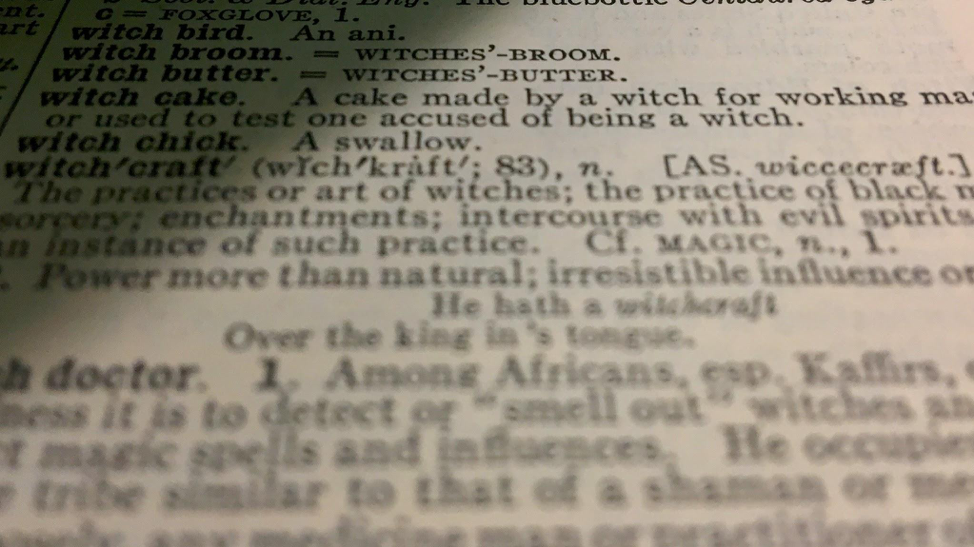

Our standard dictionary definition (pictured above) from the second edition of Webster’s New International Dictionary (1945) seemed unusually vague for a dictionary definition: “A cake made by a witch for working magic or used to test one accused of being a witch” (p. 2939). A cake made that is related to magic, in some way. Used either to create magic or confirm its malicious presence. How could it be both at once? I was intrigued.

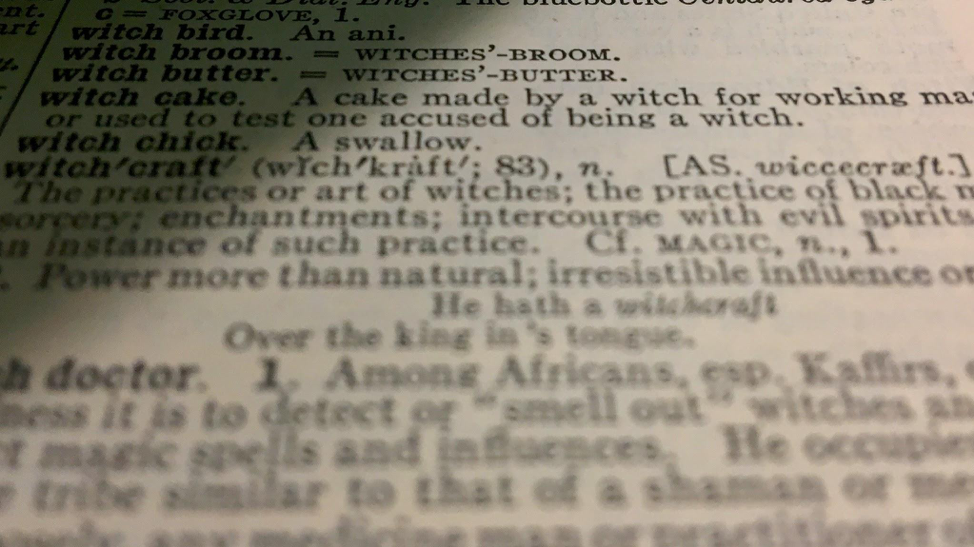

In an effort to learn more about the term itself, I went immediately to the Oxford English Dictionary, hoping it would elaborate on Webster’s definition or on the etymology of the phrase. I found it attached to the entry for the noun witch, under the subheading “Special Combinations”:

While this particular definition didn’t give as many specifics as I had hoped, I found an unexpected lead: the OED references the first use of this term in William Stewart’s Buik of the Croniclis of Scotland, first published in Middle Scots in 1535, but first edited in 1858 as a multi-volume edition in the series Rerum Britannicarum Medii Aevi Scriptores, or The Chronicles and Memorials of Great Britain and Ireland during the Middle Ages. The Rolls Series, as it is more widely known, was a mid-19th-century effort to collect and edit medieval chronicles and other historical documents, an effort proposed by the Master of the Rolls at the time.[1] In an effort to learn more about the context and the usage of the term witch cake, I began my search for the Buik itself.

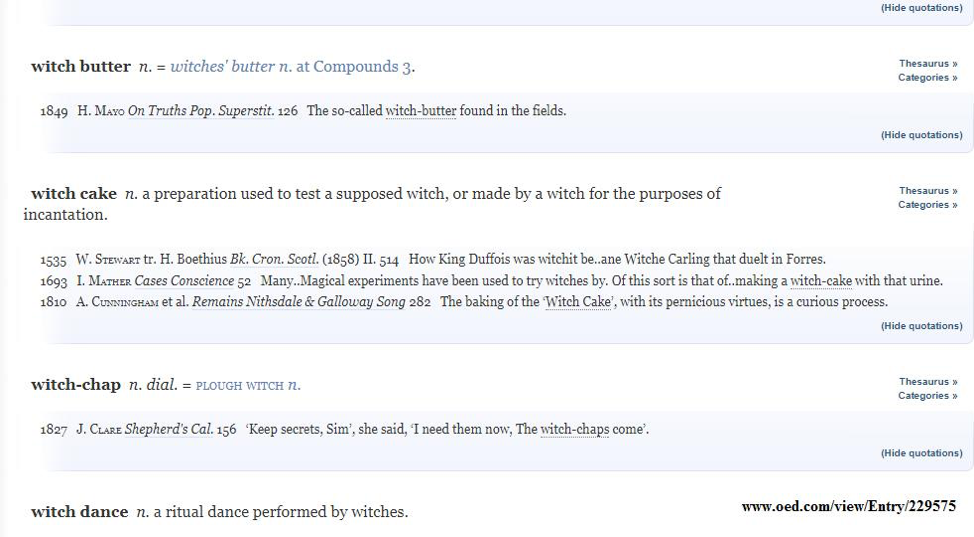

(Back wall of Robbins Library. This wall is where all series containing editions of medieval documents are kept. Such series include, but are not limited to, the Patrologia Latina, the Early English Text Society, the Scottish Text Series, and the Rolls Series.)

I expected my search to be an arduous one. But, to my delight, I found the Buik within minutes, thanks to the Robbins Library’s dedication to providing as complete holdings as possible of sources relating to all aspects of medieval studies, and in particular to such series that publish edited versions of medieval primary source documents. Although I found the exact text I needed in almost no time, what I discovered in the original Middle Scots was less than illuminating:

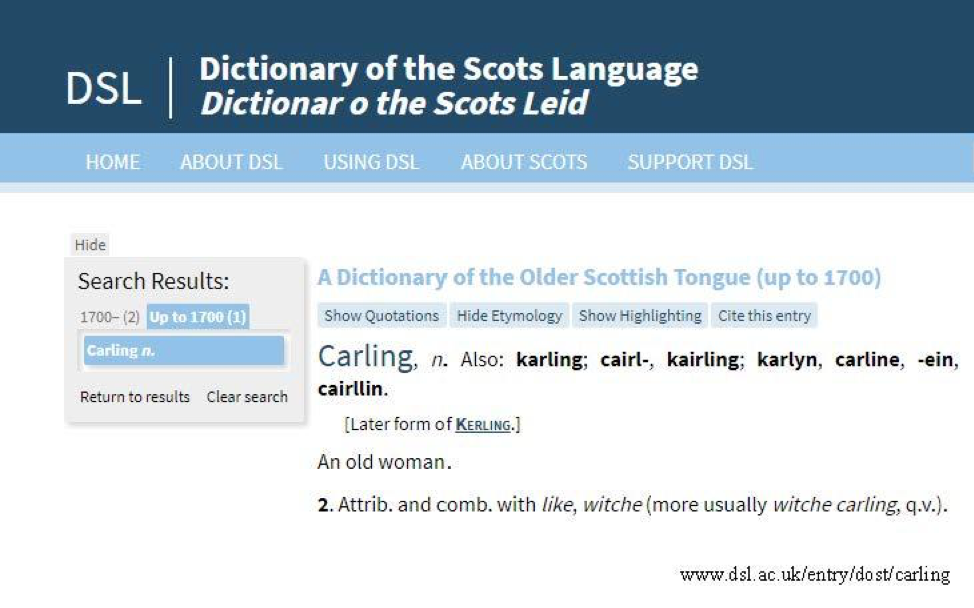

It appeared that the quote the OED referenced wasn’t part of the narrative in and of itself; instead, it was a rubric, or a heading in the document that separated episodes from each other. As best I can tell, the witch cake the OED referenced was actually “ane witche carling” -- which, according to the Dictionary of the Scots Language, actually translates approximately to an old woman who is a witch.

The rubric precedes a section where witchcraft is indeed used by an old woman -- the same “Witche Carling” named in the title -- in order to enchant King Duffois into an unnatural illness that, if left uninterrupted, would have killed the ruling monarch. The chronicle describes the act of witchcraft in the following terms:

...This ald carling vpone ane speit of tre,

Of walx ane image rostand at the fyre.

That ald trattas for turning wald nocht tyre,

And as scho turnit ay about scho sang,

Als on the image scho leit drop amang,

Out of ane pig, ane wounder fat licoir

Continuallie; … (ll. 35,846-52)

Translation:

(This old woman[,] upon a wooden spit,

Roasted a wax image on the fire.

That old woman would not tire from turning [the spit],

And as she turned [it] continually around[,] she sang,

As on the image she let drop onto [it],

A wonderful liquid fat from a pig

Continually;....)

The narrator specifically describes a wax effigy in the image of Duffois that is spitted, roasting over a fire, and continually sung over and basted with liquid pig’s fat. Later, after she is captured, the witch explains her intended results: to cause a state of feverish sleeplessness that, when the wax effigy “wer consumit haill [whole]; Quhen [when] that wes done, without ony remeid, Than force it wes to him to suffer deid” (35,880-82). While this action is definitively portrayed as witchcraft in the narrative, in no place in this section of the chronicle is the term witch cake, or any alternate Scottish spelling of the terms, used. This instance of magic uses a similar emphasis on cooking being related to the performance, and also the capture, of witches. However, it doesn’t appear to reflect the preparation of a cake. Instead, such a description invokes the image of a rotisserie-style preparation of meat over an open fire.

After poring over the Middle Scots dialect for some time, I came to the conclusion that, no, there is definitely no cake in this narrative. What is a witch cake, then? How is this term historically being used? Is there any chance that a witch cake is something that I would actually want to eat? Stay tuned to find out!!

[1] Front note to Buik of Croniclis of Scotland, vol. 2. See also M. D. Knowles’ “Presidential Address: Great Historical Enterprises IV: The Rolls Series.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 11 (1961): 137-159.

Add new comment