"The Vishakanya’s Choice”: A Conversation with Roshani Chokshi (Part 2 of 2)

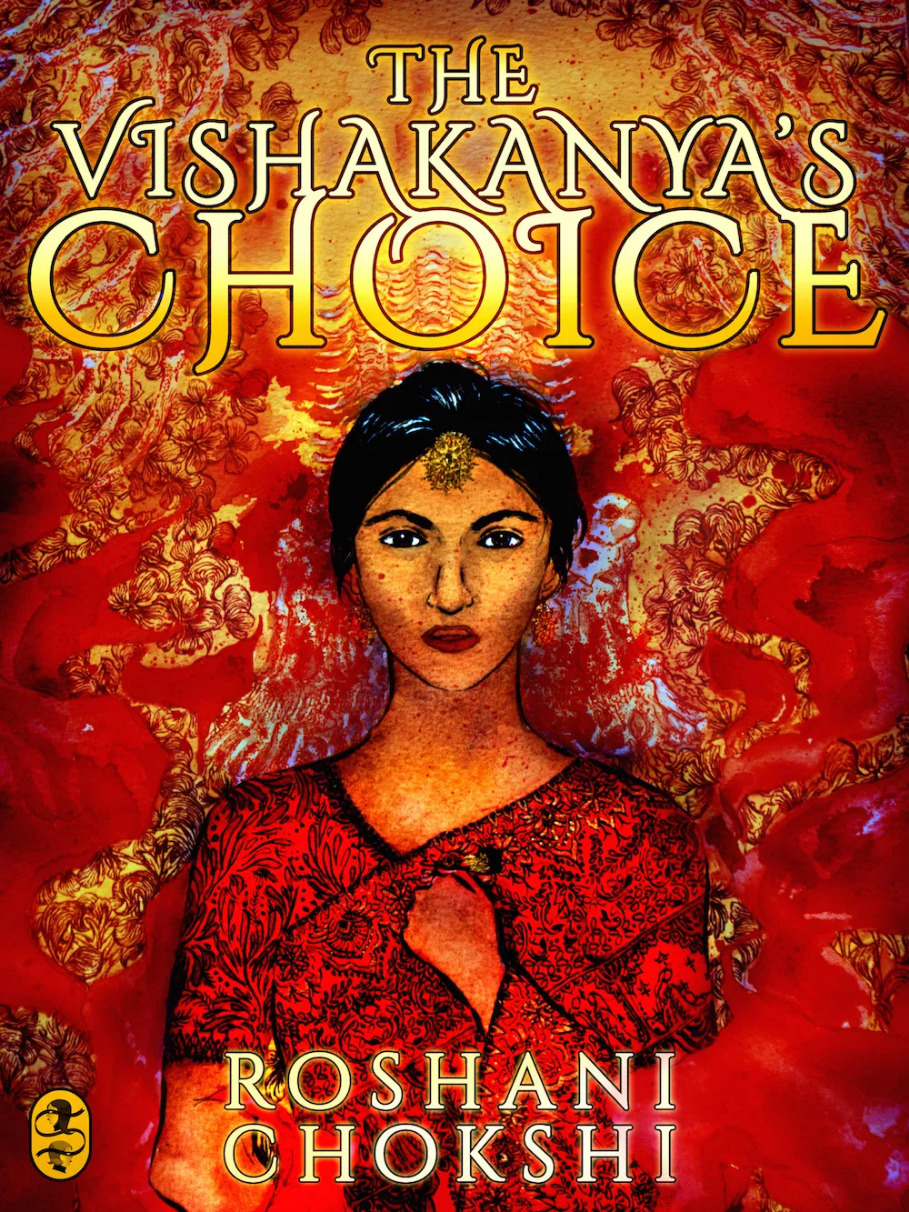

As part of the Robbins Library’s newest digital project, The Alexander Project, I sat down with New York Times bestselling author Roshani Chokshi in November of 2020 to talk about her short story, “The Vishakanya’s Choice.” This short story is a fantastical retelling of how Alexander the Great meets his demise through a vishakanya sent to infiltrate his camp and assassinate him. Vishakanyas are women (typically courtesans) who are fed poison until their very touch becomes poisonous. In versions of this story mentioned in Hindu mythology, in the pseudo-Aristotelian Secreta Secretorum, and the in medieval Latin texts such as the Gesta Romanorum, Alexander avoids death only when a trusted advisor intervenes and warns him of the danger that the maiden brings with her. In some cases, that trusted advisor is Aristotle, the renowned philosopher and Alexander’s tutor when he was young. Whereas many older versions of this story focus on Alexander the Great or on the assassination attempt itself, Chokshi gives us the perspective of Sudha, the poisonous courtesan sent to assassinate Alexander.

In the first part of our conversation (which you can read here), Chokshi and I discussed her take on Alexander, the sources that inspired her, and her approach to mythmaking. Part One ended with a contemplation on Alexander’s ability to sculpt his own reputation and how the deaths of larger-than-life personas capture people’s imagination. In Part Two, we continue to dig deeper into how Chokshi reclaims the dangerous woman stereotype through Sudha, her poisonous courtesan and the importance of controlling one’s own choices. This interview has been edited for clarity.

Steffi Delcourt (SD): This brings me to another one of the many things that I love about your story. You take something that was such a popular fascination, right. The story that’s typically told [about Alexander the Great and the poisonous courtesans] is one that’s about deception and death, and about how death is prevented but is very tantalizingly dangled in front of you, of ‘Oh no, he could have died.’ Especially with the vishakanyas tempting him. And you really turn it on its head to focus on transparency of meaning, and truth, and life, and how life goes on especially after death, in terms of not only Sudha, but also in terms of Alexander’s legend living on. A great deal of that has to do with your choice of putting Sudha front and center, rather than putting all of your focus on Alexander’s fate. I’d like to hear a little bit more about why you chose to center the story around Sudha’s fate and how she came to be as your starring protagonist.

Roshani Chokshi (RC): It’s actually a little sad. Sudha was the name of a family friend of ours, a guy I went to high school with, not a very close family friend but someone we had known a lot in the community. She was a brilliant physician, and I think she had just given birth to her second child, and she died of breast cancer shortly afterwards. And when you are that young, we, [sigh] we never forget the age at which we realize that we will die, or that people our age don’t last. And, even though I’d met her infrequently, I remembered the presence that she had, and I wanted to, I just wanted her to keep living, in a weird way. It’s not like she and I even have this personal relationship, but I think just this concept of, look at this young beautiful woman’s life that had only just started, and she had no choice in it being ripped away from her. And I think, you know, we can apply that situation to so many things, especially for the status of colonized women, particularly for women of color. Even now the scars that we bear, the burdens that we have to carry about choices being made for us before we were even able to consent to them. And so I really wanted to center it around her because when we think about who really knows history, the only people that can speak the ultimate truth of it are the ghosts. And yet we remain, and we have our stories. We have the myths that we still cling to. In vastly different ways, too. My dad is from India, and my mother is from the Philippines, and I’ve always been struck at how differently colonization treated those two countries. In India, at least there was a maintenance of temples. Those ancient works were written down. The Philippines was under Spanish rule for 400 years. I don’t even know what those indigenous last names would sound like. I don’t know the stories of those old gods. But the thing that remains and clings are the monsters, the ghosts, the things that will hurt you if you step out of line. And I guess when I was writing about Sudha, I was thinking about the way in which we reclaim even a little bit of choice, for circumstances that are outside of our control.

SD: [is sad]

RC: Yeah, I know. I hate it. And yet I often tell my dad that, at least once a year I have a panic attack in Atlanta traffic. Not unusual, because Atlanta traffic is something sent from the bowels of hell. But, I often will sometimes call my parents because I’ve had a panic attack about how I don’t want to die. [laughter] I’m like, I just don’t know. I don’t know what the fuck happens after that, I don’t want, I don’t want, [noises of existential terror, then laughter] But, my dad will always joke with me, ‘Well, you don’t want to get old or whatever, you can always die young.’ And I’m like, ‘Cool.’

RC and SD: [laughter]

SD: Very helpful there, dad.

RC: Thanks, dad. This is very much the thesis behind all of my work. I just rewrite the same story over and over again. At first I thought that was bad, but then I read this extremely sassy interview that [Vladimir] Nabokov gave to The Paris Review some time ago. He was such a jerk, I adore him.

SD: [laughter]

RC: And, somebody was saying, ‘oh, well you are always telling the same story’. And he was like, ‘Well, derivative art has other derivative art to copy. Artistic originality has only itself to emulate.’ And I was like, well, shit. [laughter] I guess I’ll just say that.

SD: I love that. And there is that concept of contemplating and confronting not only your mortality, but the mortality of humankind as a whole that I think is, like we were talking about earlier, it’s always going to be relevant. There’s so many different reactions that you can have to that. It’s whether do we respond with panic? Do we respond with despair? Do we respond with joy? It’s thinking about well what’s the nature of those responses and how do those responses then shape us as people and as characters.

RC: Absolutely. Absolutely.

SD: And again, one of the things that I absolutely adore about this story is that you have that moment continually throughout this short story. It’s never about sinking into despair, but it’s always thinking about what choices do I have [when facing mortality]? How do I claim them for my own? How do I make a better life in the face of what seems to be dangerous and scary and all-encompassing?

RC: Absolutely.

SD: Going along those lines, the vishakanya character is one that is overwhelmingly shown as dangerous, and cruel, or tempting, or deadly, especially to men. They fall into this stereotype of the monstrous feminine. I was really intrigued to see how you played with that archetype throughout. I was rereading the short story just before we were talking, and one of the lines that jumps out is Urvashi saying, “We’re weapons. We can’t afford to live.” Which is such a remarkable and also heartbreaking line. And so how do you walk that line of working within that archetype but also reclaiming it and remaking it?

RC: Well, first of all thank you. I feel so much smarter about myself every single time I talk to you, like yeah, I did do that. Good job Rosh! [laughter] There’s this phrase that has stuck with me recently; I came across it in a book called Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of Technology by Adrienne Mayor, who is fantastic. It is a Greek phrase, kalon kakon, and that translates to beautiful evil. And it was talking about Pandora and how she is essentially this automaton, beautiful automaton sent to wreak destruction and havoc etc. And I find that that’s so lazy, to make them hollow creatures.

SD: Mhmm.

RC: A long line of temptresses, you know, like Eve, etc., and all these people, and yet there are significant motivations behind why they do what they do. I am always, I have a soft spot, I think – well no, I know I have a soft spot – for what we call monstrous, things that are misunderstood, that want to be drawn into the light and held close. And I think that’s why I really wanted to engage with what we would see as the femme fatale. I think a lot of women especially, at the time I was writing this story, I forgot how old I was, but you’re thinking about the type of woman that is considered extremely desirable. And yet the woman that you want to marry and the woman that you just want to do other stuff with, the juxtaposition of the Jackie Kennedys of the world and the Marilyn Monroes, as much as the Marilyn Monroe figure is lusted after, she’s also reviled. That’s where we get words of slut-shaming, words of taunting, or other kinds of stuff. It’s so disappointing to me to see that because I think it’s always only half of a woman’s story. For me, writing Sudha and writing about what these poisonous courtesans’ lives are like allowed me to tap into what do you do when you don’t have a choice about the things that you’ve been given. If you are treated as a weapon, do you – do you make the most of it because at least it’s power? At least it gives you position in the world? Or do you spend your life trying to find a way to escape that? I don’t think that there’s a wrong answer in either of those pursuits, but, at the very least, that tension allowed me to explore who Sudha really was. I saw in her someone who, you know, I kind of was projecting the personality or the scraps of a personality of a family friend who passed away, but someone who wanted to live, to give life, to be part of other people’s lives. To not be a weapon sticking out, but part of the fabric of something greater than herself. And I think that that’s something a lot of us feel at certain points in our life: wanting to know that we are not alone.

SD: That idea of wanting to feel like you’re not alone is the ultimate pushing back against that monstrous feminine character because typically speaking, it’s always like ‘the woman.’ You look at the woman and you go, ‘Ah yes, there is danger. We will do what we want with her, but we will always treat her like an object because if she is anything more than that, then she becomes more than just a weapon. She becomes a thing that’s much more complicated and harder to dismiss out of hand. So why give the option?’

RC: Right, exactly. I mean, I think the idea of a woman being both beautiful, kind, and powerful is too subversive for the reptilian male brain. ‘Clearly, she must be bad for you.’ And it was almost funny because then, she is bad for you! She is literally poisonous. [laughter] But why does that always have to be a bad thing?

SD: Yeah. And I loved the fellowship that you created around [Sudha], even when she was at her most poisonous and her most dangerous, she was always surrounded by a harem of women who were in the exact same situation that she is and who are dealing with it in the best way that they can. And kind of offering her the comfort that they can of saying, this is the life that we have been given and so we have to make the best of it.

RC: Mhmm.

SD: And so I think it’s really interesting that I keep coming back to that line, “We’re weapons. We can’t afford to live.” That is a line that is offered as comfort; that’s in that conversation that the women have while Sudha is crying over accidentally killing a poor little kitty. And so they are talking about how she needs to effect self-care at that point. They say something along the lines of, ‘If you need to cry, you need to do it with us so we can preserve the poison. If you need to touch someone, you can touch us.’ It’s that kind of communal life, of ‘We are here for each other, and the more that you understand that we are here for each other, the stronger you will become.’

RC: Yes.

SD: Kind of.

SD: I also wanted to talk a little bit about your treatment of the red sari and how you give it a life of its own throughout the story. I don’t really have a question, it’s more of a ‘tell me more please.’

RC: I’m always fascinated by objects that seem to either have some sort of sentience or choose when to reveal themselves. It depends, I guess, what you’re reading, but Excalibur answering to Arthur’s touch if he pulls it out of the stone or the Lady of the Lake gives it to him, or something; or Harry Potter and the wand. I just like the idea that [sigh] I like the idea that we affect the space around us. And I was especially drawn to the idea of the red sari because it’s something that certainly has a lot of significance in Indian culture. That’s what I wore when I got married, was a blood-red sari. The idea is that it is a color that signifies vitality and life. To me, it was interesting because she is bound in this thing that represents life, and yet, it is not a life that she wants to live at all, so she has to break free of it, throw off its skin, and remove herself from its control.

SD: In this story you cover a lot of issues of thinking about how do we choose the life that we live, how do we choose our death as best as we can, and how do these choices not only shape who we are, but are shaped by the constrictions that are placed upon us by things like race, and gender, and whether or not we happen to be colonized. [laughter]

RC: Yeah, I mean, like, that is, I imagine that is such a huge thing, right? You want to keep living in this kingdom, what do you say, like, ‘This is the best dude I’ve ever met?’ kind of thing? Like, ‘Let me through.’ There’s always an exchange in that narrative. Who is a good ruler? How do we really know? These are the only people who you have left to talk about it. [laughter] So, I’m always, always fascinated by that, and I’m fascinated by people who have rich afterlives. I wonder about the people that they interacted with, the unsung heroes and heroines who beat that entire age just by being happy. What a subversive, radical thing. To be happy. To be happy with your choices.

You can read Chokshi’s short story here: https://www.thebooksmugglers.com/2015/08/the-vishakanyas-choice-by-roshani-chokshi.html. And you can find more from Roshani Chokshi at her website: www.roshanichokshi.com.