L'Affaire Schlauch

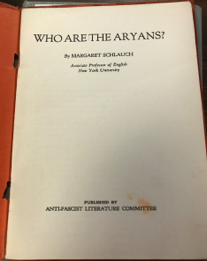

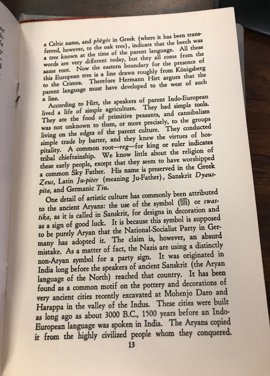

In the 1940s and ‘50s, the spectre of communism was haunting America. America responded with a series of witch hunts aimed at ridding institutions of suspected Communist Party members and sympathizers, culminating in the now infamous HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee) led by Senator Joseph McCarthy. Margaret Schlauch, a respected linguist and medievalist at New York University, was among those named in 1941 during the Rapp–Coudert Committee — “a dress rehearsal for the McCarthyism of the 1950’s on the national scene” — which sought to expunge any communists from the New York City public school system. (1) Although she denied being a member of the Party at that time, Schlauch’s left-leaning, anti-fascist political views would have been obvious. In the publication Who Are the Aryans? (c. 1940), Schlauch uses her knowledge as a linguist and historian to systematically dismantle the Nazi’s mythographic arguments for the Aryans’ racial superiority.

Schlauch maintained her teaching position until early 1951 when it became clear that the Red Scare was not going away. Realizing that living in America would mean having to sacrifice either her convictions or her academic career, Schlauch fled to Poland where her sister- and brother-in-law had recently relocated. (2) In doing so, she preempted the fallout of Party-defector Bella V. Dodd’s 1952 testimony, in which she identified numerous teachers were communists who “enslaved the minds of certain Americans through the educational process,” just as she herself once did. (3) Among those named were Helen Ann Mins Robbins, wife of Rossell Hope Robbins, and her brother Henry Felix Mins, Jr., whose professional lives were indeed ruined by the allegations. (4) In Poland, however, Schlauch could construct her career anew, teaching medieval English literature at the University of Warsaw (Uniwersytet Warszawa) and publishing numerous articles in both English and Polish.

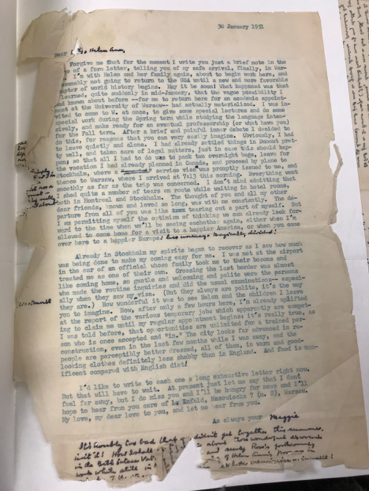

Yet, Schlauch stayed in contact with her friends and former colleagues. The Robbins Library houses over 100 letters written by Margaret Schlauch to Rossell and Helen Ann. The letters are among the only surviving records of Schlauch’s life as an expat medievalist. (5)

In a form letter dated 31 January 1951, she informs her friends that she has left the country — possibly forever — having travelled first to Canada and then to Stockholm before finally arriving in Warsaw.

I’m with Helen and her family again, about to begin work here, and presumably not going to return to the USA until a new and more favorable chapter of world history begins. May it be soon! What happened was that I learned, quite suddenly in mid-January, that the vague possibility I had known about before — for me to return here for an academic appointment at the University of Warsaw — had actually materialized. I was invited to come to W[arsaw] at once, to give some special lectures and do some special work during the Spring term while studying the language intensively, and make ready for an eventual professorship (or what have you) for the Fall term. After a brief and painful inner debate I decided to do this, for reasons that you can very easily imagine. Obviously, I had to leave quietly and alone. I had already settled things in Dumont pretty well, and taken care of legal matters, just in case this should happen; so that all I had to do was to pack two overnight bags, leave for the vacation I had already planned in Canada, and proceed by plane to Stockholm, where a "special" service visa was promptly issued to me, and thence to Warsaw[. …] The thought of you and all my other dear friends, known and loved so long, was with me constantly. The departure from all of you was like [?] tearing out a part of myself. But I am permitting myself the optimism of thinking we can already look forward to the time when we'll be seeing eachother [sic] again, either when I'm allowed to come home for a visit to a happier America, or when you come over here to a happier Europe.: [lives] uneasy & tragically divided!

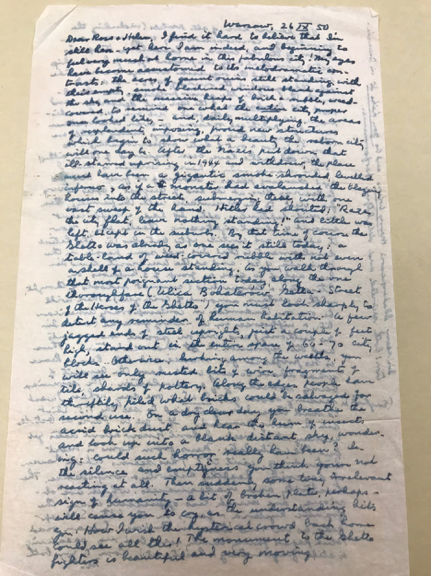

Even knowing the reasons for her departure, it is still rather astonishing that Schlauch fled, having seen firsthand the devastation of the city that she would eventually call home. In a letter dated 26 September 1950, written during the trip on which she established the “vague possibility” of professorship, she poignantly describes Warsaw, a city still struggling to rebuild after it was literally “razed” by Nazi troops seven years prior.

[…] My eyes have become accustomed to its melodramatic contrasts: the acres of gaunt ruins still standing, with their empty smoke-blackened windows blank against the sky and the massive heaps of brick & rubble, weed-covered, to remind one what the entire city proper once looked like, — and, daily multiplying, the areas of resplendent, imposing, proud new structures which begin to show what a beauty the reborn city will one day be. After the Nazis put down that ill-sta[rte]d uprising in 1944 and withdrew, the place must have been a gigantic smoke-shrouded, levelled inferno, as if a [?] monster had avalanched the blazing houses into the streets, submerging these, with one vast sweep of the hand. Hitler had shouted: “Raze the city flat, leave nothing standing!” And little was left, except in the suburbs. By that time of course the Ghetto was already as one sees it still today: a table-land of weed-covered rubble with not even a shell of a house standing. As you walk through that most poignant section today, along the one thoroughfare (Ulica Bobaterów Ghetta — “Street of the Heroes of the Ghetto”) you must look sharply to detect any reminder of human habitation: a few jagged ends of steel uprights, just a couple of feet high, stand out in the entire space of 60–70 city blocks. Otherwise, lurking among the walls, you will see only rusted bits of wire, fragments of tile, shards of pottery. Along the edges, people have thriftily piled what bricks could be salvaged for second use. On a dry clear day you breathe the acrid brick dust and hear the hum of insects and look up into a blank distant sky, wondering: could such horror really have been? In the silence and empt[i]ness you think you’re not reacting at all. Then suddenly some tiny irrelevant sign of humanity — a bit of broken plate, perhaps — will cause you to cry, as the understanding hits you. How I wish the hysterical crowd back home could see all this! The monument to the Ghetto fighters is beautiful and very moving.

The “new and more favorable chapter of world history” that Schlauch had once hoped for did not come soon enough, and she died in Warsaw on 21 July 1986. Robbins strove to publish the letters, but his own death in 1989 prevented the project’s completion. Recognizing the relevance of the letters to today’s political climate, however, the Robbins Library has begun to transcribe and digitize the letters. They should all be available by the end of this year.

(1) Edel, The Struggle for Academic Democracy.

(2) Richmond, “Margaret Schlauch and American Studies in Poland During the Cold War,” pp. 53–54.

(3) Committee on the Judiciary, Subversive Influence in the Educational Process, pp. 38–39.

(4) Helen Ann and her brother Henry Felix Mins, Jr., both members of the Teachers’ Union, were called to testify before the Senate Committee. Helen Ann never answered the subpoena and retired early on the basis of legitimate disabilities caused by a horseback riding injuries in adolescence. The official record states that she was in Croton-on-Hudson, New York, caring for her ailing mother (Committee on the Judiciary, Subversive Influence in the Educational Process, p. 53). However, according to Russell Peck, who knew them both personally, the couple immediately embarked on a cross-country roadtrip to avoid answering her subpoena. Over the next few years, they stayed with various family friends, and Robbins took single-semester teaching jobs at colleges along the way to make ends meet.

(5) See Rose, “Margaret Schlauch (1898–1986),” pp. 534–35.

Works Cited

Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate. Subversive Influence in the Educational Process: Hearings before the Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, Eighty-Second Congress, Second Session on Subversive Influence in the Educational Process. September 8, 9, 10, 23, 24, 25, and October 13, 1952. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1952.

Edel, Abraham. The Struggle for Academic Democracy: Lessons from the 1938 “Revolution” in New York’s City Colleges. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1990.

Richmond, Yale. “Margaret Schlauch and American Studies in Poland during the Cold War.” The Polish Review 44.1 (1999): 53–57.

Rose, Christine M. “Margaret Schlauch (1898–1986).” In Women Medievalists and the Academy. Ed. Jane Chance. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2005.

Schlauch, Margaret. Who Are the Aryans? New York: Anti-Fascist Literature Committee, n.d. [1939/40?]